Throughout my life, I have turned to the arts for comfort, healing, entertainment and distraction. Dance and music, in particular, have always been part of my being - a true love, if you will. Growing up, I put together soundtracks with different songs for different situations and occasions, choreographed at all hours of the night, and I wallpapered my teenage bedroom in Rolling Stone covers. Music makes sense to me because it mirrors life: the melodies that rise and fall the same way mood ebbs and flows, the rhythms that help move you along or insist you wait patiently, and my favorite part - the mindful silence between the notes that offers a chance to reflect and simultaneously beckons you to listen closely for what comes next. Music is for celebrating and grieving. It’s for letting go and understanding ourselves and finding one another. The infinity of music is the closest thing to magic that I can imagine.

I’ve also always been a planner, so it was no surprise I took the linear steps from high school right into college, then teaching music, and then becoming a therapist. But it took a leap of faith to do something outside of the box, and I have Dissonance co-founder, David Lewis, to thank for pushing me to go there. In 2012, David and I spent a lot of moments with our work team at a small music college scratching our heads, wondering how to best support musicians who wanted to make a life in the arts. They were grappling with how-to’s, feasibility, and their own becoming as young people. Many were also struggling with addiction, mental illness, grief, and identity on top of the typical growing pains. We realized we needed to make it ok to talk about this stuff in public on our campus and to do so in an accessible way, through music. We had our method: a panel with notable musicians who would talk about their own mental health. We just needed a name.

On a walk back to campus after having one of our deep planning talks (my favorite) at the Amsterdam (his favorite), "Dissonance" clicked in my head. I screamed it at David out of nowhere, and it was quickly a done deal. In psychology, dissonance is the discomfort of holding or perceiving conflicting beliefs. In music, dissonance is the discomfort or tension of clashing pitches. In both, we seek resolution—i.e. to resolve the discomfort. And that was exactly it for our students: they were pushing toward a developmental leap in their work with us - whether in counseling or career services - and trying to make sense of the discomfort that comes with growth.

When the college started to reduce services for students and my position was cut, I knew it was worth fighting for the rights to Dissonance — both the name and our concept. The idea for a nonprofit was born when David and I gathered a passionate group of professionals who would later become our founding board members. We all voted to start a 501(c)3 organization and did so in 2016, which means we celebrated five years in summer 2021!

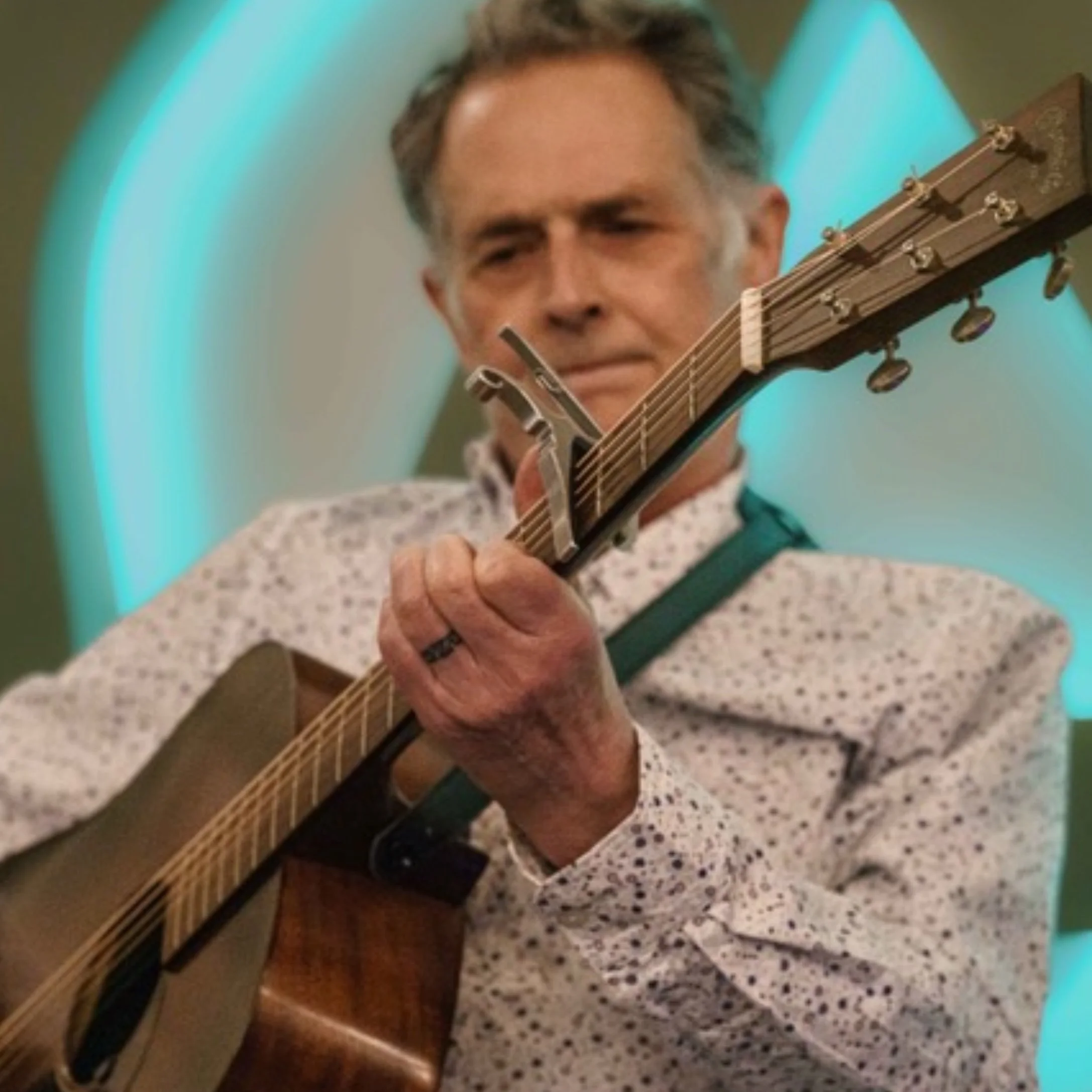

When artists continue saying yes to our events and new folks reach out to be involved, that’s a sign we are on the right path. When individuals contact us about the support they have found through our Get Help Directory, it solidifies our goal of linking folks to mental health and recovery resources. And when educators and organizations share our handouts or invite us into their spaces, you can hear the stigma crumbling.

I can talk endlessly about the cool stuff we have done, the outstanding roster of artists who have played with us, and the inspiring stories we have heard (read the many other posts on this blog for more!). But the most meaningful part of Dissonance to me personally at this moment in time is the lesson that I don't have to keep myself at arms length as a leader here. As the Chair of the Board, I used to unintentionally treat Dissonance as something I oversaw and made nice for others. When I was forced to set a boundary with my time during winter 2021 due to personal life challenges, I finally admitted to the rest of the board that I was afraid to step back, to let go. That’s when they all insisted that I rest and promised to carry on until I was ready for next steps. That acceptance told me everything I needed to know about the community we have created together. Talk about an “aha” moment! It was then I realized this thing I nurtured for everyone else over the years was exactly what - and who - my current self needed.

It is fair to say I am in awe of the relationships forged in the name of Dissonance and the human beings who offer themselves up to not only our shared cause but to me as a person. In fact, I think some might even appreciate me more for my vulnerability than for my management skills. The Dissonance embrace has been incredibly humbling, enlightening and healing. I practice gratitude for these authentic relationships daily and feel inspired to keep going and growing because of them.

Our mission of supporting mental health and recovery in and through the arts includes everyone. We all have a mental health story and are all touched by addiction in some way. We also all benefit from the arts in our lives, without a doubt. I am so incredibly proud of the small spark of an idea that has grown into a steady heartbeat here in the Twin Cities. Over time, we’ve been incredibly fortunate to welcome new voices to our board, each of whom has contributed to our evolution as an organization. Our volunteers, artist alumni, event attendees, blog readers, and community collaborators all make Dissonance what it is at any given moment.

Dissonance combines my passions for creativity, wellness, and relationships, and it’s an honor to be part of this with all of you. I invite anyone reading to check out our monthly Story Well group, attend events, and contribute to our blog. Please also consider Dissonance in your giving plans or come volunteer with us! And stay tuned for our next meaningful and fun project, Dissonance Sessions, which will bring out stories behind the music in a fresh new way that reaches more people and brings us all together. More magic.

Sarah Souder Johnson, MEd, LPCC, is co-founder and chair of the board for Dissonance, and a mental health therapist at Sentier Psychotherapy.